Not-for-Profit Healthcare:

Challenges Remain, Opportunities Arise

- Not-for-profit healthcare is a complex and diverse sector that touches many aspects of our lives.

- The pandemic both created and exacerbated economic headwinds that will continue to buffet the sector, even as it continues to recover and evolve.

- There are opportunities to enhance portfolio returns through a fastidious credit-research process and selection of high-quality healthcare bonds.

Investing in Not-for-Profit Healthcare

The municipal bond market touches almost every aspect of our daily lives. Roads, bridges, airports, and seaports are built with bonds — as are the reservoirs that store clean drinking water for cities and towns across the country and the transmission lines that deliver electricity to our homes and businesses. Further, the market provides funding for the K-12 school districts educating our children and to the universities that drive groundbreaking research and prepare our young people for productive roles in society.

The market has a surprisingly long history — the first bond was issued by the State of New York in 1812 to finance the Erie Canal. In addition, the market’s capitalization is massive at $4 trillion with nearly 100,000 distinct issuers. Ownership of municipal bonds is broad-based; individual investors, banks, insurance companies, and overseas investors are all active in the market.

Healthcare is a municipal sector that often slips under the radar, although healthcare itself pervades many aspects of our lives, whether through maternity, pediatric, or preventative care; urgent or emergency care; cancer or other specialty care; or end-of-life/hospice care. The sector is often misunderstood or overlooked due to its complexity and perceived risk. Moreover, the last few years have been very challenging as hospitals and healthcare systems continue to battle through the effects of the pandemic and the economic headwinds left in its wake.

The following is an overview of the municipal healthcare sector, which in addition to playing a critical role in our everyday lives, is also an important component of Bessemer client bond portfolios.

What Are Not-For-Profit Hospitals and Healthcare Systems?

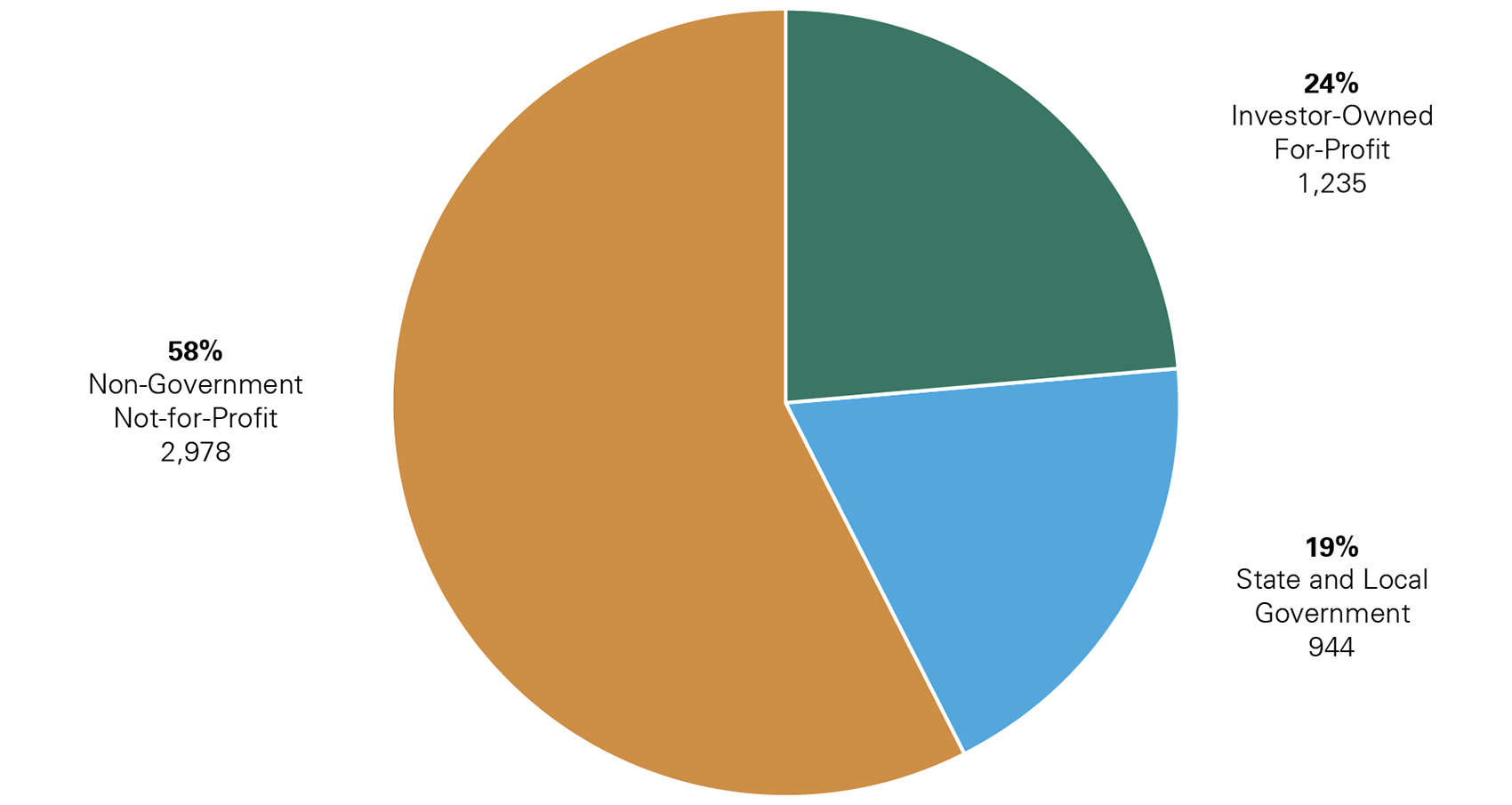

According to the American Hospital Association, as of May 2023, there were 5,157 community hospitals in the United States: 2,978 were not-for-profit community hospitals, 1,235 were for-profit community hospitals, and 944 were state and local government community hospitals (Exhibit 1).

Economic Headwinds Facing the Healthcare Sector

- Labor shortages.

- Increased cost of labor due to temporary (agency) staffing.

- Lost revenue due to canceled surgical procedures.

- Inflated supply costs.

- Nontraditional entrants to healthcare market.

Exhibit 1: Community Hospitals by Ownership Type

Key takeaway: Most community hospitals in the U.S. are not-for-profit hospitals.

Source: American Hospital Association, Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2023,

https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

Broadly speaking, hospitals in the United States can be classified as either for-profit or not-for-profit. For-profit hospitals and healthcare systems are investor-owned corporations and, as such, cannot issue bonds in the municipal market. These corporations are operated in the most efficient manner to maximize quarterly performance, profits, and shareholder value, which may at times conflict with the best interests of the communities served.

In contrast, not-for-profit hospitals and healthcare systems are service and mission driven. Many have religious affiliations and trace their roots back over 100 years. These institutions are tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organizations and can issue in both the taxable and tax-exempt markets. In exchange, not-for-profit hospitals and systems must provide charity care and reinvest a percentage of profits in the communities in which they operate. Not-for-profits include single- and multi-state acute care providers, pediatric hospitals, academic medical centers, and safety-net hospitals.

Community hospitals include hospitals providing general and specialty services (e.g., rehabilitation; orthopedics; eye, ear, nose, and throat, etc.) as well as academic medical centers/other teaching hospitals. Excluded are hospitals not accessible by the general public (e.g., prison hospitals or college infirmaries) and hospitals owned/operated by the federal government.

501(c)(3) organizations are commonly referred to as charitable organizations. The primary purpose of a 501(c)(3)s is to serve the public interest; examples include universities, museums/other arts organizations, research/charitable foundations, and not-for-profit healthcare providers.

Not-for-profits — particularly safety-net hospitals — serve a greater number of medically and financially vulnerable patients and, as a result, provide more uncompensated care. Therefore, not-for-profits tend to carry higher levels of bad debt than their for-profit counterparts.

Differences Between the Not-For-Profit Healthcare Sector and Other Municipal Sectors

Not-for-profit healthcare has traditionally been considered a specialty sector of the municipal market, offering significant diversity in terms of issuer geography, size, and services provided. Moreover, in part due to inherent differences in state regulations (which can be changed by state legislatures/regulators), the features that make a not-for-profit healthcare issuer attractive in one state might not render an issuer attractive in another.

In addition, in a number of respects, the sector is more aligned with the corporate market than with the municipal market. As is the case for corporate healthcare issuers, the revenue streams of not-for-profit hospitals/healthcare systems tend to exhibit greater volatility than the revenue supporting the typical municipal issuer (i.e., patient care revenue versus far more predictable taxes/fees). Further, financial disclosure is generally released quarterly rather than annually (which is customary for municipal issuers), and management has a more corporate-like structure than that employed by the typical governmental issuer.

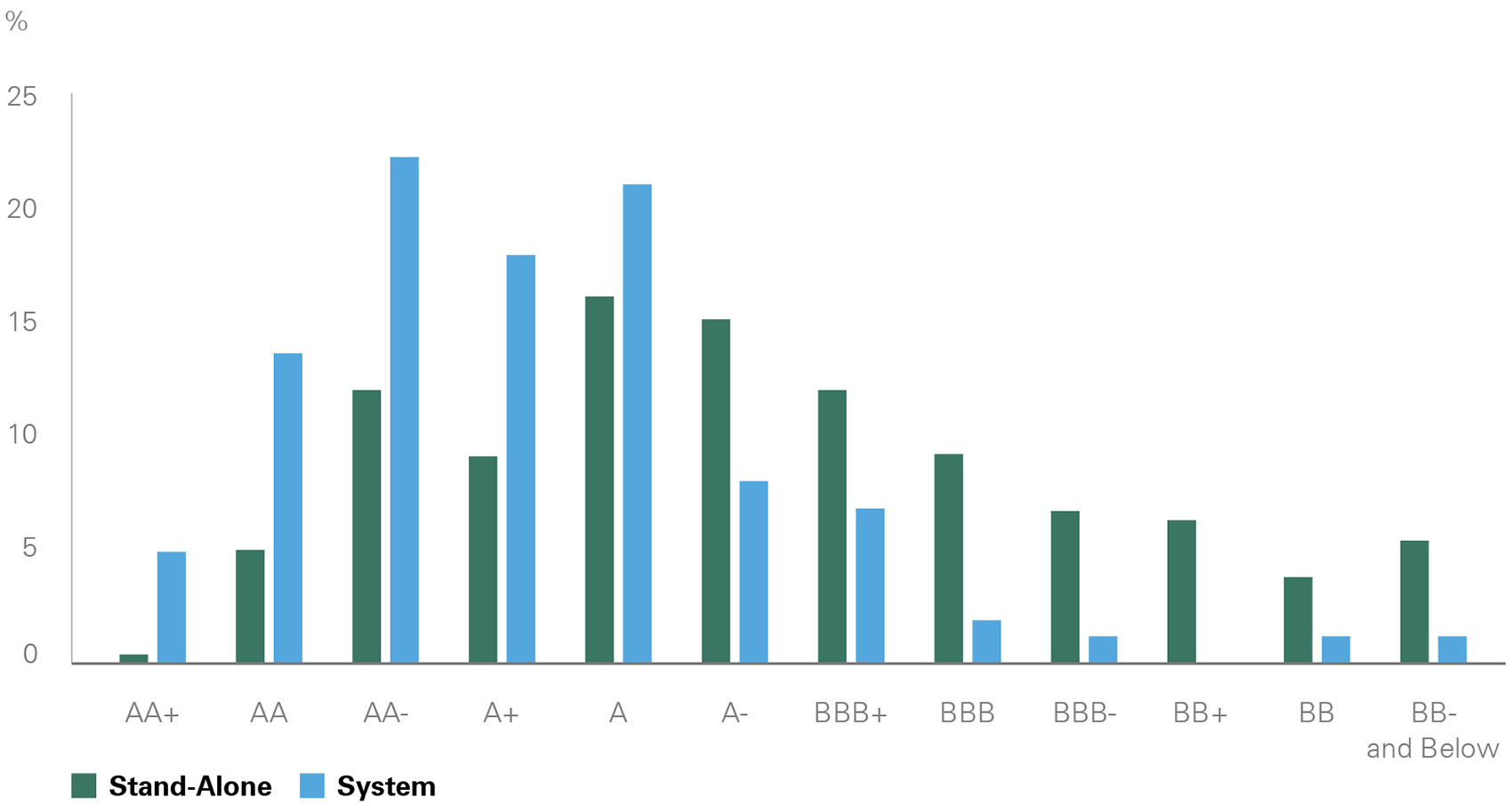

In terms of credit ratings, there are no triple-A rated hospitals or healthcare systems, and very few issuers are even rated in the upper double-A category (Exhibit 2). In contrast to other municipal sectors (and more akin to the corporate market), a higher percentage of issuers are rated in the triple-B and non-investment-grade categories. Credit ratings are also less stable than the ratings of other governmental issuers. Therefore, surveillance must be more rigorous than is the case for the municipal market, in general.

Although there is a de facto rating ceiling for not-for-profit hospitals/healthcare systems, and ratings generally trend lower versus many other municipal sectors, opportunities do exist to purchase high-quality healthcare bonds through active management and a thorough knowledge of the breadth and depth of the sector, its history, and the evolving business models of not-for-profit hospitals and healthcare systems. Through careful selection and regular surveillance, the risks associated with this complex sector can be lessened.

Exhibit 2: Not-For-Profit Healthcare Rating Distribution

Key takeaway: Not-for-profit healthcare ratings skew lower than the ratings of other sectors of the municipal market – aligning the sector with corporate counterparts.

Key Takeaway: Not-for-profit healthcare ratings skew lower than the ratings of other sectors of the municipal market – aligning the sector with corporate counterparts.

Source: S&P Global Ratings

Types of Hospitals

Academic medical centers are hospitals or healthcare systems that are affiliated with medical schools and provide graduate medical education along with cutting-edge research and clinical care.

Acute care hospitals focus solely on the treatment and care of people with short-term medical needs such as surgery, obstetrics, and various illnesses; chronic or long-term care is generally not managed by acute care hospitals.

Pediatric hospitals cater primarily to children between the ages of 0 and 14. Facilities, equipment, and patient care are specialized to meet their needs.

Safety-net hospitals primarily serve the most medically and financially vulnerable populations.

Specialty hospitals provide a limited service or set of services; examples include cancer care, cardiac, orthopedics, and women’s health.

Post-Pandemic Recovery

The pandemic and its aftermath created one of the most significant challenges ever encountered by the healthcare sector. Supply chain issues, overcrowding, labor shortages, and burnout, in addition to the strain of responding to a new, unknown pathogen, washed over the sector like a tsunami.

While many of these difficulties have abated, the healthcare sector will continue to face a shortage of doctors, nurses, and general support staff, and plans are being developed by leadership teams to address this issue. To tackle the high cost of labor experienced in 2022 and early 2023, attracting, training, and retaining nurses will be a primary focus of most hospitals and healthcare systems. Although not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels, labor costs should stabilize in 2024 to a more manageable, albeit higher, level as post-pandemic contract negotiations come to an end.

We expect a continuation of hospital closures, particularly in rural settings, and consolidations, often across state lines. However, mergers and acquisitions will face increased scrutiny at the federal and state levels. As not-for-profit hospitals and healthcare systems work toward differentiation versus competitors and strive to both increase revenue and lower costs, joint ventures and affiliations could provide strategic opportunities, especially for services outside the walls of the hospital.

Recent Trends: Bessemer Equity Team’s Perspective

Bessemer equity portfolios aim to invest in companies directly impacted by evolving trends in the healthcare industry as the investment world emerges from the pandemic. Two important themes that have noticeable implications for the team’s healthcare investments include the continued transition to value-based care arrangements and the recovery of utilization – with procedures increasingly being performed in non-hospital care settings. Bessemer is invested across companies that portfolio managers believe will benefit from these shifting dynamics which will provide tailwinds for continued growth.

The team believes that UnitedHealth Group, a Bessemer holding, is accelerating the shift to fully accountable value-based care, delivering higher member engagement and improved health outcomes. Its value-based care arrangements aim to deliver better experiences for patients and care providers, improve health outcomes, and lower total cost of care. A recently published peer-reviewed study found that Medicare Advantage patients enrolled in the company’s fully accountable care model showed materially better health outcomes compared to Medicare Fee-for-Service programs. The results are made possible by the broad capabilities of Optum Health, its care provider network, including its interoperable platforms and technology, scalable operating model, and comprehensive care network. Looking ahead, the team believes Optum’s impressive competitive advantage will continue to strengthen.

Another prevailing trend across multiple healthcare industries involves the rate at which people re-engage with the healthcare system, specifically their return to surgical procedures. Utilization trends dropped meaningfully during the early days of the pandemic, particularly in the senior patient cohort which felt less comfortable seeking care at out-patient facilities and hospitals. Fast forward to the present and the industry is beginning to experience an increase in healthcare benefit utilization, especially among seniors that previously postponed care around areas such as orthopedic and cardiovascular surgical procedures. Managed care organizations, providing insurance benefits to this population, have recently commented on these elevated outpatient utilization trends, highlighting increased hip and knee procedures occurring in ambulatory surgical centers for its Medicare Advantage membership base. At the same time, rising utilization is a tailwind for medical device companies that provide the equipment and technology for these surgeries. Portfolio companies Johnson & Johnson, Intuitive Surgical, Medtronic, and Abbott Laboratories have experienced robust procedure volume growth year-to-date as pent-up demand from the first years of COVID return to the industry.

Into the Future: Recent Trends in the Healthcare Sector

As the healthcare sector recovers from the wreckage wreaked by Covid, a few major trends are emerging in healthcare reimbursement, delivery, and revenue diversification. Increasingly, nontraditional players are stepping into the healthcare space, most notably Amazon and CVS. Though some of these trends were developing pre-Covid, the pandemic accelerated and, in some cases, reshaped them.

Fee Structures and Payment Models

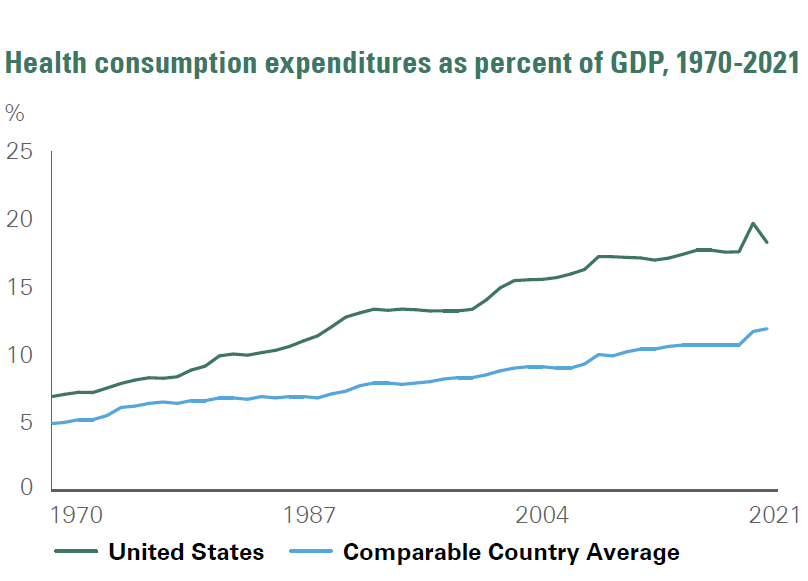

Fee-for- service. Many providers in the U.S. healthcare system are paid under a fee-for-service structure. Fee-for-service reimbursement, by its nature, creates perverse incentives as providers are paid based on the quantity of care provided, rather than the quality. In fact, the United States spends a greater percentage of its GDP on healthcare versus its developed international peers (see Exhibit 3). Medicare and Medicaid, the two governmental programs, are examples of fee-for-service models.

Value-based care, community care, and population health. The leading alternative to fee-for-service reimbursement is value-based care. Under this methodology, healthcare providers are assessed on quality measures (such as readmission rates). This shifts the incentives; for example, providers receive higher payments (e.g., from health insurers) for administering care that will have a positive impact on patient health and are penalized with lower payments for poor outcomes.

Population health and community care refer to healthcare organizations’ focus on identifying social determinants of health impacting their patient bases and developing programs to alleviate health inequality. The World Health Organization defines the social determinants of health as “the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.” These “factors” include income or employment, food insecurity, educational attainment, social inclusion, and housing. The breadth of innovation in this space speaks to its significance in the healthcare sector. As an example, Virtua Health, based in southern New Jersey, operates a mobile grocery store and farmers’ market to provide fresh produce to community members at heavily subsidized prices.

Exhibit 3: U.S. and Peer Health Expenditures Relative to GDP

Key takeaway: The current standard for physician reimbursement in the United States has significantly inflated healthcare spend relative to the same metric in global peer countries.

The current standard for physician reimbursement in the United States has significantly inflated healthcare spend relative to the same metric in global peer countries.

Source: KFF analysis of National Health Expenditure (NHE) and OECD data

Opportunities to Diversify Revenue

In the post-Covid healthcare market, operating a hospital (or network of hospitals) will no longer be sufficient to maintain a competitive position. By expanding points of contact in local communities, hospitals and healthcare systems can not only chip away at competitors’ market share, but they can also establish new revenue streams to reduce reliance on payments derived from in-hospital patient care.

Alternative points of contact could be clinical and include ambulatory surgery centers, diagnostic imaging centers, freestanding laboratory services, and primary care offices. New delivery methods such as telehealth can expand a provider’s footprint beyond the immediate physical surroundings — though, notably, there are limits to the types of care that can be administered digitally (e.g., behavioral health as opposed to orthopedics), and insurance coverage is far from universal.

There are even more opportunities for hospitals and systems that venture beyond the clinical sphere. A relatively common business line among not-for-profit providers is insurance. Some hospitals and healthcare systems establish relationships with regional commercial insurers; alternatively, providers can create new insurance products and contract with local employers to offer such products as part of employee benefit packages. Insurance can serve as a hedge against volatility in clinical revenues and expand a provider’s reach beyond its physical location(s).

Medicare and Medicaid

Medicare and Medicaid are government insurance programs that were originally signed into law in 1965. Medicare eligibility is determined at the federal level and covers individuals aged 65 or older, as well as people with disabilities and end-stage renal disease. While the federal government establishes regulations for Medicaid (the governmental program designed to serve low-income individuals), there is a good deal of latitude in the implementation of Medicaid at the state level. For example, Medicaid eligibility varies from state to state based on income and family size and whether or not low-income adults without children are covered.

Nontraditional Entrants

In addition to competition from other hospitals and healthcare systems, healthcare providers are facing increasing threats from nontraditional players entering, and potentially disrupting, the market. Two recent examples are Amazon’s acquisition of One Medical and CVS’s acquisition of Aetna.

One Medical specializes in primary care, and its offerings include 24/7 virtual care, prescription refills, mental health services, and urgent care. Importantly, prior to being acquired by Amazon, One Medical already had a significant presence in the highly lucrative employer market, a segment Amazon failed to penetrate with its Amazon Care arm. This is an example of “horizontal integration” — Amazon is expanding the breadth of services it offers by acquiring One Medical.

In contrast, CVS’s acquisition of Aetna is an example of “vertical integration.” CVS is linking its existing network of pharmacies with Aetna’s healthcare provider network; the providers write the prescriptions that CVS pharmacies dispense. Since the healthcare provider, pharmacy, and insurer are now controlled by one organization, the patient experience, in theory, should be relatively seamless versus the provision of services by unaffiliated entities.

A common link between these two nontraditional entrants is that neither offers inpatient care; both seek to improve primary care and outpatient services. Outpatient services are less costly to administer than inpatient care, and the capital requirements are lower (e.g., there is no need to construct and equip a hospital). Further, by focusing on primary and outpatient care, these entrants avoid the regulatory burden associated with inpatient care.

Putting It All Together; Examples of Systems We Like

As previously noted, the not-for-profit healthcare sector is confronting a number of challenges. However, in-depth credit analysis can uncover attractive (and stable) issuers. Discussed below are two healthcare systems Bessemer has reviewed for client portfolios.

An integrated healthcare system considers the physical, emotional, behavioral, and financial aspects of healthcare. The goal is to offer patients comprehensive care (including preventative measures for various chronic illnesses – e.g., diabetes) to improve patient outcomes and lower healthcare costs.

SSM Health (SSM) is a fully integrated regional healthcare system headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. SSM owns and operates facilities in Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin and has affiliations with 33 rural hospitals. The system is rated A+ by S&P and AA- by Fitch Ratings.

One attribute Bessemer finds particularly attractive is SSM’s ability to successfully adapt to the evolving healthcare market. For example, the composition of SSM’s revenue base has changed over the past 10 years. According to disclosure provided by SSM, inpatient services made up 51% of revenue in 2012 versus 29% in 2022. Labor costs have also been effectively managed as evidenced by a 41% decline in hourly clinical agency rates (the expense primarily associated with temporary or traveling nurses) since the start of 2022. While SSM did not escape the sector-wide financial decline of 2022, SSM has stabilized faster than many other not-for-profit healthcare systems due to the diversity of its operating model.

Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian (Hoag), rated AA by S&P and Fitch, is a regional healthcare system based in Orange County, California. The system includes two acute care hospitals, a joint venture specialty hospital, 15 urgent care centers, and 10 health centers. Hoag had been affiliated with Providence Health & Services (based in Washington), but in January 2022, Hoag (viewed as the strongest member of the Providence system) ended the affiliation.

Once the affiliation was dissolved, Bessemer began to monitor Hoag’s standalone financial performance. The system’s operations have rapidly improved from the havoc wrought by the pandemic, and Hoag continues to be characterized by a strong management team and a healthy cash position. Bessemer views the system as an opportunity in the California market where it can be challenging to find attractive healthcare issuers.

Conclusion

One of the foundational principals of portfolio management is appropriate diversification, and in the context of a municipal bond portfolio, this translates into investing across a variety of municipal sectors, issuers and structures — including healthcare. Although healthcare may not garner as much investor attention as other sectors of the market, there are compelling reasons for inclusion in portfolios. Undeniably, healthcare providers across the nation will continue to face challenges associated with (and exacerbated by) the pandemic; however, the operations and finances of fundamentally sound healthcare issuers are beginning to recover from the low point experienced in 2022.

Nonetheless, the headwinds buffeting the sector since the onset of the pandemic continue to cause market dislocations. As a result, high-quality, liquid healthcare bonds can trade at lower prices and wider credit spreads than would be the case under more “normal” (pre-pandemic) market conditions. Bessemer’s dedicated healthcare analysts are able to navigate this complex and evolving municipal sector, providing an excellent opportunity to add high-quality healthcare bonds with the goal of enhancing portfolio returns.

With contributions from Nicholas Cedrone and Erica Zhou.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This material is provided for your general information. It does not take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual clients. This material has been prepared based on information that Bessemer Trust believes to be reliable, but Bessemer makes no representation or warranty with respect to the accuracy or completeness of such information. This presentation does not include a complete description of any portfolio mentioned herein and is not an offer to sell any securities. Investors should carefully consider the investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses of each fund or portfolio before investing. Views expressed herein are current only as of the date indicated, and are subject to change without notice. Forecasts may not be realized due to a variety of factors, including changes in economic growth, corporate profitability, geopolitical conditions, and inflation. The mention of a particular security is not intended to represent a stock-specific or other investment recommendation, and our view of these holdings may change at any time based on stock price movements, new research conclusions, or changes in risk preference. Index information is included herein to show the general trend in the securities markets during the periods indicated and is not intended to imply that any referenced portfolio is similar to the indexes in either composition or volatility. Index returns are not an exact representation of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index.